|

Специальные ежемесячные бизнес-журналы для руководителей крупных предприятий России и СНГ

|

|

Окна из алюминия в Севастополе — это новые возможности при остеклении больших площадей и сложных форм. Читайте отзывы. Так же рекомендуем завод Горницу.

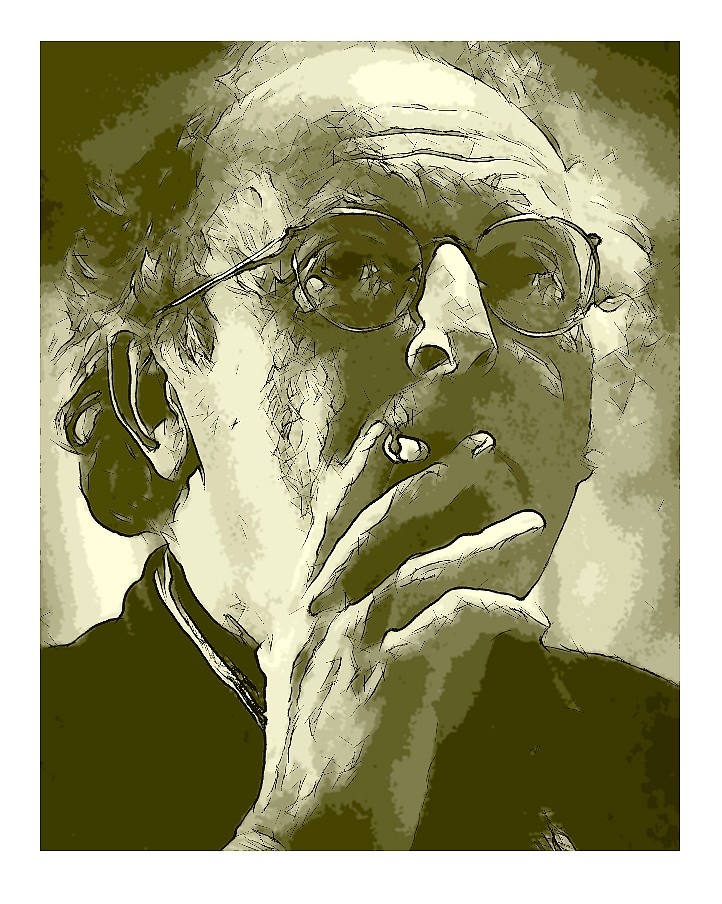

Страницы сайта поэта Иосифа Бродского (1940-1996)

Иосиф Бродский

Компьютерная графика - А.Н.Кривомазов, март 2011 г.

</<br />

</<br />

Из письма луны М.:

К. пригласила на ужин членов расширенного Совета, потом показала один из первых

твоих вестернов на четвертом этаже - "Одинокий ствол". Странно, я раньше этот фильм

пропустила. Сценарист, режиссер и главная кинодива - ЛФ. Там много драк, стрельбы,

нервного крутого смеха и десяток ослепительных постельных сцен. Оказалось, никто

раньше, кроме К., тоже этого фильма не видел... Потом проверила фильмотеку - всегда

был в свободном доступе... Но их там столько... А теперь их вообще - дурная бесконечность...

Даже странно - умнейшие люди наших Островов их создавали в какой-то бешеной горячке -

тысячи могилок мальчиков сгорели безвозвратно... В этом фильме ты играешь не просто

одинокого охотника, но Зверобоя, сердце которого ранила дочь богача, в роскошных

спальнях особняка которого проходит половина фильма, другая половина - твоя великолепная

стрельба, невозмутивмая ирония и желчные шутки, отлично поставленные драки и т.п. и т.д.

Порылась в архиве и штрих-пунктиром просмотрела "Сварливую жену", где ты играешь Сократа.

Познавательно! Получается, ЛФ чуть ли не наизусть знает "Диалоги" Платона... Могилки!!! Ц. М.

January 29, 1996

Joseph Brodsky, Exiled Poet Who Won Nobel, Dies at 55

By ROBERT D. McFADDEN

Joseph Brodsky, the persecuted Russian poet who settled in

the United States in the early 1970's, won the Nobel Prize

for Literature in 1987 and became his adopted country's

poet laureate, died yesterday at his apartment in Brooklyn

Heights. He was 55.

The cause was believed to be a heart attack, said Roger

Straus, Mr. Brodsky's friend and publisher. Mr. Brodsky had

open-heart surgery in 1979 and later had two bypass

operations, and had been in frail health for many years.

The poetry of Joseph Brodsky, with its haunting images of

wandering and loss and the human search for freedom, was

not political, and certainly not the work of an anarchist

or even of an active dissident. If anything, his was a

dissent of the spirit, protesting the drabness of life in

the Soviet Union and its pervasive materialist dogmas.

But in a land of poets where poetry and other literature

was officially subservient to the state, where verses were

marshaled like so many laborers to the quarries of

Socialist Realism, it was perhaps inevitable that Mr.

Brodsky's wark -- unpublished except in underground forums,

but increasingly popular -- should have run afoul of the

literary police.

He was first denounced in 1963 by a Leningrad newspaper,

which called his poetry "pornographic and anti-Soviet." He

was interrogated, his papers were seized, and he was twice

put in a mental institution. Finally he was arrested and

brought to trial.

Unable to fault him on his poetry's content, the

authorities indicted him in 1964 on a charge of

"parasitism." They called him "a pseudo-poet in velveteen

trousers" who failed to fulfill his "constitutional duty to

work honestly for the good of the motherland."

The trial was held in secret, though a transcript was

smuggled out and became a cause celebre in the West, which

was suddenly aware of a new symbol of artistic dissent in a

totalitarian society. Mr. Brodsky was found guilty and

sentenced to five years in an Arctic labor camp.

But amid protests from writers at home and abroad, the

Soviet authorities commuted his sentence after 18 months,

and he returned to his native Leningrad. Over the next

seven years he continued to write, with many of his works

translated into German, French and English and published

abroad, and his stature and popularity continued to grow,

particularly in the West.

But he was increasingly harassed, for being Jewish as well

as for his poetry. He was denied permission to travel

abroad to writers' conferences. Finally, in 1972, he was

issued a visa, taken to the airport and expelled. He left

his parents behind.

With the help of W. H. Auden, who befriended him, he

settled in Ann Arbor, Mich., where he became a

poet-in-residence at the University of Michigan. He later

moved to New York, teaching at Queens College, Mount

Holyoke College and other schools. He traveled widely,

though never back to his homeland, even after the collapse

of the Soviet Government. He became a United States citizen

in 1977.

Meanwhile, his poems, plays, essays and criticisms appeared

in many forums, including The New Yorker, The New York

Review of Books and other magazines. They were anthologized

in books in a growing canon that garnered the 1981

MacArthur Award, the 1986 National Book Critics Circle

Award, an honorary doctorate of literature from Oxford

University and, in 1987, the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The Swedish Academy, which awards the prestigious prize,

said he had been honored for the body of his work and "for

all-embracing authorship, imbued with clarity of thought

and poetic intensity." It also called his writing "rich and

intensely vital," characterized by "great breadth in time

and space."

In 1991, the United States added to his honors, naming him

poet laureate. The rumpled, chain-smoking Mr. Brodsky had

for 15 years been the Andrew Mellon Professor of Literature

at Mount Holyoke College, in South Hadley, Mass., and had

been scheduled to return there today to begin the spring

semester.

Joseph Ellis, a former faculty dean who brought Mr. Brodsky

to the college in the early 1980's, recalled yesterday how

his friend often was seen speeding around the campus in an

old Mercedes. He would interrupt conversations with

students and colleagues to jot down notes on bits of paper

he carried in his pocket. "He thought out loud in front of

his students in a way that was inspirational," Mr. Ellis

said.

Mr. Brodsky, who wrote in English as well as in Russian,

though his poems were composed in Russian and

self-translated, was a disciple of the Russian poet Anna

Akhmatova, whom he called "the keening muse." He was also

strongly influenced by the English poet John Donne, as well

as Mr. Auden, who died in 1973. One volume of Mr. Brodsky's

poetry, "Elegy to John Donne and Other Poems," was

published in London in 1967. His "Selected Poems" had a

foreword by Mr. Auden.

But Mr. Brodsky was best known for three books published by

Farrar, Straus & Giroux: a volume of poetry called "A Part

of Speech" (1977); a book of essays, "Less Than One"

(1986), which won the National Book Critics Circle Award,

and a book of poems, "To Urania" (1988). Other recent works

include a play in three acts called "Marbles" (Noonday

Press, 1989) and a book of prose, "Watermark" (Farrar,

Straus, 1992).

Mr. Straus remembered Mr. Brodsky as "very warm, very

caring, very willing to give his friendship," especially to

young writers and other exiles, some of whom he championed

selflessly.

Robert Silvers, co-editor of The New York Review of Books,

also spoke in glowing terms of Mr. Brodsky and his work.

"It was astonishing that a Russian poet should have emerged

as also one of the most powerful writers in the English

language in just these years of exile," he said.

In Russia, Yevgeny Kiselyov, host of the weekly news

program Itogi, told the nation's te'evision viewers: "He

was the only Russian poet who enjoyed the right to be

called 'great' in his lifetime."

It was also reported in Moscow that Gleb Uspensky, a senior

editor and co-publisher of the Russian publishing house

Vagrius, had met Mr. Brodsky in New York last fall and

asked him to return to Russia for a tour as part of a deal

to republish some of his works in Russian. Mr. Uspensky was

quoted as saying that Mr. Brodsky seemed interested, but

was torn by the prospect and did not agree.

Joseph Aleksandrovich Brodsky -- whose first name is

sometimes given as Josip or Iosif -- was born in Leningrad

on May 24, 1940, to Joseph Aleksandrovich Brodsky, a

commercial photographer, whose status as a Jew kept him

often out of work, and Maria M. Volpert Brodsky, who was

linguistically gifted and often supported the family.

The redheaded boy spent his early years living in a

communal apartment shared with other families. His parents

gave him a Russified, assimilated upbringing, and he

himself made little of his religious lineage, but as he

later recalled, his teachers were anti-Semitic and treated

him negatively.

However, he was something of a spiritual dissenter, even as

a boy. "I began to despise Lenin, even when I was in the

first grade, not so much because of his political

philosophy or practice . . . but because of his omnipresent

images," he recalled.

He quit school at the age of 15 and began working in what

proved to be a series of jobs, including laborer, metal

worker and hospital morgue attendant. Literature provided

an alternative to the drabness of his life. He learned

Polish so he could translate the works of Polish poets like

Czeslaw Milosz, and English so he could translate Donne.

Beginning in 1955, he began to write poems, many of which

appeared on mimeographed sheets, known as samizdat, and

were circulated among friends. Others were published by a

fringe group of young writers and artists in the

underground journal Sintaksis.

He began joining street-corner recitations, rendering his

poems in a voice that was soft yet dramatic, reflecting the

weariness and vibrancy in his verses. "He recited as if in

a trance," one friend recalled. "His verbal and musical

intensity had a magical effect." As his popularity began to

grow, he a'so made enemies among older, more entrenched

Leningrad writers.

In 1963, after a Leningrad newspaper denounced the

23-year-old poet as "a drone" and "a literary parasite,"

harassments began in a pattern that seemed to confirm that

they had official backing. These led to a trial that began

in February 1964. A transcript sent to the West contained

this colloquy:

Judge: What is your profession?

Brodsky: Translator and poet.

Judge: Who has recognized you as a poet? Who has enrolled

you in the ranks of poets?

Brodsky: No one. Who enrolled me in the ranks of the human

race?

Found guilty and given a sentence of five years, Mr.

Brodsky was sent to a labor camp near Arkhangelsk, where he

chopped wood, hauled manure and crushed rocks for 18

months. At night, in his bunk, he read an anthology of

English and American poetry.

After his release and return to Leningrad, the harassment

resumed, but so did his work, and some of it began

appearing in the West. "Verses and Poems" was published by

the Inter-Language Literary Associates in Washington in

1965, "Elegy to John Donne and Other Poems" was published

in London in 1967 by Longmans Green, and "A Stop in the

Desert" was issued in 1970 by Chekhov Publishing in New

York.

Despite his growing stature, however, he was denied

permission to attend writers' conferences abroad. In 1971,

he received two invitations to immigrate to Israel. In May

1972, he was summoned to the Ministry of the Interior and

asked why he had not accepted. He said he had no wish to

leave his country.

Within 10 days, authorities invaded his apartment, seized

his papers, took him to the airport and put him on a plane

for Vienna. In Austria, he met Mr. Auden, who arranged for

his transit to the United States. After a year at Michigan

as poet-in-residence, he taught at Queens College

(1973-74), returned to the University of Michigan (1974-80)

and then accepted a chair at Mount Holyoke.

Mr. Straus recalled that he was with Mr. Brodsky in London

when they learned about the Nobel Prize. "He was

overjoyed," Mr. Straus recalled. "It was fairly amazing

that Joseph should win at that young age." But publicly,

Mr. Brodsky made light of it. "A big step for me, a small

step for mankind," he joked.

In naming him United States poet laureate in 1991, James

Billington, the Librarian of Congress, said Mr. Brodsky

"has the open-ended interest of American life that

immigrants have. This is a reminder that so much of

American creativity is from people not born in America."

Mr. Brodsky is survived by his wife, Maria, and his

daughter, Anna, who were with him when he died.

A Poet in His Own Words

Everything has its limit, including sorrow.

A windowpane stalls a stare. Nor does a grill abandon

a leaf. One may rattle the keys, gurgle down a swallow.

Loneliness cubes a man at random.

A camel sniffs at the rail with a resentful nostril;

a perspective cuts emptiness deep and even.

And what is space anyway if not the

body's absence at every given

point? That's why Urania's older than sister Clio!

In daylight or with the soot-rich lantern,

you see the globe's pate free of any bio,

you see she hides nothing, unlike the latter.

-- From the title poem of the collection "To Urania"

Darling, you think it's love, it's just a midnight journey.

Best are the dales and rivers removed by force,

as from the next compartment throttles "Oh, stop it,

Bernie,"

yet the rhythm of those paroxysms is exactly yours.

Hook to the meat! Brush to the red-brick dentures,

alias cigars, smokeless like a driven nail!

Here the works are fewer than monkey wrenches,

and the phones are whining, dwarfed by to-no-avail.

Bark, then, with joy at Clancy, Fitzgibbon, Miller.

Dogs and block letters care how misfortune spells.

Still, you can tell yourself in the john by the spat-at

mirror,

slamming the flush and emerging with clean lapels.

-- From "Seaward," in the collection "To Urania"

Citizen, enemy, mama's boy, sucker, utter

garbage, panhandler, swine, refujew, verrucht;

a scalp so often scalded with boiling water

that the puny brain feels completely cooked.

Yes, we have dwelt here: in this concrete, brick, wooden

rubble which you now arrive to sift.

All our wires were crossed, barbed, tangled, or interwoven.

Also: we didn't love our women, but they conceived.

Sharp is the sound of the pickax that hurts dead iron;

still, it's gentler than what we've been told or have said

to ourselves.

-- From "Letter to an Archeologist," in the collection "To

Urania"

So long had life together been that now

the second of January fell again

on Tuesday, making her astonished 'row

lift like a windshield wiper in the rain,

so that her misty sadness cleared, and showed

a cloudless distance waiting up the road.

-- From "Six Years Later," in the collection "A Part of

Speech"

I was born and grew up in the Baltic marshland

by zinc-gray breakers that always marched on

in twos. Hence all rhymes, hence that wan flat voice

that ripples between them like hair still moist,

if it ripples at all. Propped on a pallid elbow,

the helix picks out of them no sea rumble

but a clap of canvas, of shutters, of hands, a kettle

on the burner, bo'ling -- lastly the seagull's metal

cry. What keeps hearts from falseness in this flat region

is that there is nowhere to hide and plenty of room for

vision.

Only sound needs echo and dread its lack.

A glance is accustomed to glance back.

-- From the title poem in the collection "A Part of Speech"

For some odd reason, the expression "death of a poet"

always sounds somewhat more concrete than "life of a poet."

Perhaps this is because both "life" and "poet," as words,

are almost synonymous in their positive vagueness. Whereas

"death" -- even as a word -- is about as definite as a

poet's own production, i.e., a poem, the main feature of

which is its last line. Whatever a work of art consists of,

it runs to the finale which makes for its form and denies

resurrection. After the last line of a poem nothing follows

except literary criticism. So when we read a poet, we

participate in his or his works' death. In the case of

Mandelstam, we participate in both.

-- From "The Child of Civilization," in "Less Than One: Selected Essays"

Источник: http://www.nytimes.com/books/00/09/17/specials/brodsky-obit.html?_r=2&scp=9&sq=Joseph%20Brodsky&st=cse

Иосиф Бродский

I

"Он был настолько дерзок, что стремился

познать себя..." Не больше и не меньше,

как самого себя.

Для достиженья этой

недостижимой цели он сначала

вооружился зеркалом, но после,

сообразив, что главная задача

не столько в том, чтоб видеть, сколько в том,

чтоб рассказать о виденном голландцам,

он взялся за офортную иглу

и принялся рассказывать.

О чем же

он нам поведал? Что он увидал?

Он обнаружил в зеркале лицо, которое

само в известном смысле

есть зеркало.

Любое выраженье

лица - лишь отражение того,

что происходит с человеком в жизни.

А происходит разное:

сомненья,

растерянность, надежды, гневный смех -

как странно видеть, что одни и те же

черты способны выразить весьма

различные по сути ощущенья.

Еще страннее, что в конце концов

на смену гневу, горечи, надеждам

и удивлению приходит маска

спокойствия - такое ощущенье,

как будто зеркало от всех своих

обязанностей хочет отказаться

и стать простым стеклом, и пропускать

и свет и мрак без всяческих препятствий.

Таким он увидал свое лицо.

И заключил, что человек способен

переносить любой удар судьбы,

что горе или радость в равной мере

ему к лицу: как пышные одежды

царя. И как лохмотья нищеты.

Он все примерил и нашел, что все,

что он примерил, оказалось впору.

II

И вот тогда он посмотрел вокруг.

Рассматривать других имеешь право

лишь хорошенько рассмотрев себя.

И чередою перед ним пошли

аптекари, солдаты, крысоловы,

ростовщики, писатели, купцы -

Голландия смотрела на него

как в зеркало. И зеркало сумело

правдиво - и на многие века -

запечатлеть Голландию и то, что

одна и та же вещь объединяет

все эти - старые и молодые - лица;

и имя этой общей вещи - свет.

Не лица разнятся, но свет различен:

Одни, подобно лампам, изнутри

освещены. Другие же - подобны

всему тому, что освещают лампы.

И в этом - суть различия.

Но тот,

кто создал этот свет, одновременно

(и не без оснований) создал тень.

А тень не просто состоянье света,

но нечто равнозначное и даже

порой превосходящее его.

Любое выражение лица -

растерянность, надежда, глупость, ярость

и даже упомянутая маска

спокойствия - не есть заслуга жизни

иль самых мускулов лица, но лишь

заслуга освещенья.

Только эти

две вещи - тень и свет - нас превращают

в людей.

Неправда?

Что ж, поставьте опыт:

задуйте свечи, опустите шторы.

Чего во мраке стоят ваши лица?

III

Но люди думают иначе. Люди

считают, что они о чем-то спорят,

поступки совершают, любят, лгут,

пророчествуют даже.

Между тем,

они всего лишь пользуются светом

и часто злоупотребляют им,

как всякой вещью, что досталась даром.

Одни порою застят свет другим.

Другие заслоняются от света.

А третьи норовят затмить весь мир

своей персоной - всякое бывает.

А для иных он сам внезапно гаснет.

IV

И вот когда он гаснет для того,

кого мы любим, а для нас не гаснет

когда ты можешь видеть только лишь

тех, на кого ты и смотреть не хочешь

(и в том числе, на самого себя),

тогда ты обращаешь взор к тому,

что прежде было только задним планом

твоих портретов и картин -

к земле...

Трагедия окончена. Актер

уходит прочь. Но сцена - остается

и начинает жить своею жизнью.

Что ж, в виде благодарности судьбе

изобрази со всею страстью сцену.

Ты произнес свой монолог. Она

переживет твои слова, твой голос

и гром аплодисментов, и молчанье,

столь сильно осязаемое после

аплодисментов. А потом - тебя,

всё это пережившего.

V

Ну, что ж,

ты это знал и раньше. Это - тоже

дорожка в темноту.

Но так ли надо

страшиться мрака? Потому что мрак

всего лишь форма сохраненья света

от лишних трат, всего лишь форма сна,

подобье передышки.

А художник -

художник должен видеть и во мраке.

Что ж, он и видит. Часть лица.

Клочок какой-то ткани. Краешек телеги.

Затылок чей-то. Дерево. Кувшин.

Все это как бы сновиденья света,

уснувшего на время крепким сном.

Но рано или поздно он проснется.

<1971>

* На киностудии "Леннаучфильм" в шестидесятые годы кормилось немало

отверженных: ученые, идеи которых не признавала академическая наука,

литераторы, которые нигде не печатались и выживали благодаря сценарной

работе. Однажды ко мне, редактору студии, подошел режиссер Михаил

Гавронский. Он вывел меня в коридор, дал несколько листков со стихами и

сказал: "Это написал мой племянник Ося. Ему нужно как-то зарабатывать:

родители очень волнуются, что он без дела". Было это в 1962 году. Стихи

показались мне замечательными, и, когда ко мне пришел молодой Иосиф

Бродский, мы стали вместе думать, что бы ему написать.

* Он предложил сделать фильм о маленьком буксире, который плавает по

большой Неве. Через месяц он принес стихи о буксире и сказал, что это и есть

сценарий. К сожалению, нам пришлось отказаться от темы, потому что было

ясно, что Госкино никогда не утвердит сценарий в таком виде. Иосиф же

сказал, что написал все, что мог. Через год, еще до ссылки, стихи о буксире

были опубликованы в детском ленинградском журнале. Эта единственная

публикация не имела, конечно, никакого значения для судебного решения по

поводу "тунеядства" поэта.

* В 1971 году, пользуясь давностью знакомства, я обратился к Иосифу

Бродскому с просьбой написать текст в стихах к фильму "Рембрандт. Офорты".

Иосиф прочитал мой режиссерский сценарий и сказал, что попробует. Через две

недели я пришел к нему и получил четыре страницы стихов. Он пообещал: "Это

проба. Когда фильм будет отснят, я напишу больше". Фильм был снят, а стихи

отвергнуты сценарным отделом студии "Леннаучфильм": Бродский уже был

"слишком известной" фигурой. Стихи так и остались у меня; копии у автора не

было, единственный экземпляр был отдан мне в руки прямо с машинки. Сейчас

эти стихи Иосифа Бродского публикуются впервые.

Виктор КИРНАРСКИЙ

* "Московские новости". No. 5. 1996

</<br />

На пляже.

Компьютерная графика - А.Н.Кривомазов, март 2011 г.

</<br /> </<br />

Карта сайта: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15.

|